The following article is an excerpt from the new edition of “In Review by David Ehrlich,” a biweekly newsletter in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the site’s latest reviews and muses about current events in the movie world. Subscribe here to receive the newsletter in your inbox every other Friday.

There comes a time in everyone’s life when they have to plan and host a glitzy movie awards show, and for me, that time came earlier this week when I — in my role as chair of the New York Film Critics Circle —emceed this year’s NYFCC awards dinner at Tao Downtown in Manhattan. In addition to corralling luminaries like Ben Stiller, Lupita Nyong’o, and Mikhail Baryshnikov to present the awards to our winners, my responsibilities also included kicking things off with some introductory remarks about the evening’s purpose.

Every chair approaches that part of the program in their own way; some have done schtick, others have been more straightforward. As anyone familiar with my work knows all too well, it’s a lot more comfortable for me to ramble on for thousands of words than it is to be concise, and so the only way I could steady myself in a situation as nerve-wracking as this one was to hold half of Hollywood hostage for a long, long speech about the relationship between critics and filmmakers. So long, in fact, that Jafar Panahi and Paul Thomas Anderson both later roasted me about it from the stage, with the latter declaring that, for the next calendar year, I’ve forfeited the right to criticize movies for their length. Just to make sure that I can never repress the memory, I’ve conveniently been provided with a picture of the exact moment that happened:

The only silver lining is that the speech was so long that IndieWire Editorial Director Kate Erbland, knowing that I would be too exhausted to write anything else this week, suggested that I just publish the text as the lead piece of this week’s “In Review” newsletter. And so that’s what I’ve done.

My guess is that it’s less punishing to get through in print, but if you want to recreate the vibe of sitting through it live at the NYFCC dinner, feel free to read it aloud to yourself in an extremely crowded restaurant full of your colleagues and heroes.

***

Hello! My name is David Ehrlich, and it’s my great pleasure and profound anxiety to welcome you to the 91st New York Film Critics Circle Awards. You would never know it from my Victorian skin pallor, a physique that makes Marty Supreme look like The Smashing Machine, or from the fact that I own the entire Criterion Collection despite living paycheck-to-paycheck, but I am indeed a film critic; to my wonderful mother, who is in the room tonight, I’m so sorry that you had to find out this way. If it’s any consolation, mom, had I become a doctor or a lawyer I would never have been able to lend you a heavily watermarked For Your Consideration DVD of Brendan Fraser’s fish-out-of-water drama “Rental Family,” so at least there’s something you can still brag about to your friends.

Of course, we are not here this evening to discuss my disappointments as a human being — there are truly so many different spaces on the internet where you can do that on your own time. But this is my time, for better or worse, and I’m afraid to say that I’m going to drag it out for another 10 to 12 minutes; like several of our winners tonight, I simply don’t know how to do anything short, but my promise to you is that this won’t be the worst thing that’s ever happened in this country on January 6th. Top five, maybe.

Anyway, back to the topic at hand. Many of the year’s best movies and performances were unexpected in one respect or another. After firmly establishing herself as one of the great comedic talents of her generation, Rose Byrne blew us all away with her nerve-shredding dramatic performance in “If I Had Legs I’d Kick You.” After 13 years of absence following her unforgettable 2011 narrative film “The Loneliest Planet,” Julia Loktev returned with a monumental documentary about the last independent journalists in Russia. And after several decades of shamelessly appealing to the masses with multiplex slop like “Phantom Thread,” “Inherent Vice,” and “There Will Be Blood,” Paul Thomas Anderson finally made something for the critics. Well done, Paul, thank you for throwing us a bone at last.

Of course, “One Battle After Another” would be a fitting descriptor of what the movies have faced since their first invention. Cinema as a medium has always been defined by its persistence: the persistent illusion of motion that allows a quick succession of still images to assume the quality of a dream, the persistent hold that it maintains over our imaginations in the face of invasive new technologies, and the persistent faith that it projects onto the power of communal experiences, even at a time when reality itself is being siloed into a series of discrete echo chambers (shoutout to “Eddington”).

I’m reminded of that persistence as I reflect on a year of tumult, loss, and potentially catastrophic self-destruction within the film community. This doesn’t feel like the right time to elaborate on that last point, but — on a completely unrelated note — I would like to congratulate Netflix and Warner Bros. for combining to win almost half of our awards tonight.

In 2025, we lost David Lynch, Robert Redford, and Souleymane Cissé. We lost Diane Keaton, Diane Ladd, and Tatsuya Nakadai. We lost the war against the word “casted,” the fight against taking pictures of the screen, and whatever remaining foothold documentaries had in the theatrical marketplace. Indeed, for the second consecutive year, our winner for Best Non-Fiction Film is more likely to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature than it is to receive proper distribution. Yes, “My Undesirable Friends: Part I — Last Air in Moscow” is five-and-a-half hours long and filled with some of the ugliest and most upsetting things you’ll ever see on screen, but neither of those factors stopped “Wicked: For Good” from grossing more than $500 million, and so I can’t fathom why they would be such dealbreakers for Julia Loktev.

Most of all, too many of my colleagues lost their jobs as a result of employers who failed to appreciate their value, and the depth of their readers’ connection to their voices, and the entire community is poorer for that.

And yet, this was also a year that epitomized cinema’s tradition of persistence. Specifically, the persistence of historical memory, as we saw in films like “It Was Just an Accident,” “The Secret Agent,” and, in its own way, the elegiacally quotidian baseball drama “Eephus,” whose writer/director, Carson Lund, has worked as a critic himself, and has actually reviewed the work of some of our other winners tonight. Quite well, I might add. And positively, which might be even more important.

Try as I might, it’s hard to be all doom and gloom about a year that gave us the single most unstoppable movie soundtrack since “Saturday Night Fever,” two Bronstein family classics, and “a few small beers” for good measure. So while it may seem a bit “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic” to get dressed up and celebrate film in the growing shadow of technocratic greed, unabated genocide, and the AI-generated perversion of image-making itself, I don’t think it’s wholly unimportant that the movies of 2025 were really, really fucking great. Or that we are gathering here tonight to acknowledge them as such in the face of these imperiled times.

That is what the New York Film Critics Circle has done through thick and thin for the last 91 years, which some might choose to see as a remarkable display of persistence in its own right. We bravely gave our awards during periods of strife as painful and varied as World War II, the Great Recession, and the Isiah Thomas era of the New York Knicks, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all of those things ended on our watch.

Perhaps I’m giving critics too much credit for our role in shaping modern history, and in shaping the art that it’s produced. Then again, perhaps the rest of you aren’t giving us enough. That film critics and filmmakers depend on each other is self-evident, but I think that critics are unfairly often seen as the barnacles rather than the whales.

The sacred task of the critic is to provoke and entertain the masses, to introduce them to new worlds, to stoke the imaginations of children, to inspire generations of dreamers, to excite people about the possibility of being alive, and to challenge them to engage with the world in a variety of radically empathic new ways. And the simple job of the filmmaker is just to give the critic something to write about. And I don’t mean to diminish that! Somebody has to do it. You kindly provide us with crude eruptions of light and sound, and we do the hard — some would say holy — work of shaping that chaos into layers of meaning.

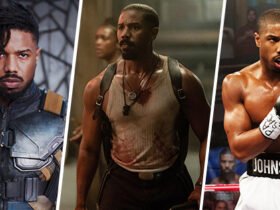

Allow me to illustrate my point. Much as I enjoyed “Eephus,” we all know that movie was really just 99 minutes of under-employed character actors standing around on a field until Nick Schager called it “a new sports-movie classic, as sneakily effective as the pitch which gives it its title.” Beautifully shot as it was by our Best Cinematography winner Autumn Durald Arkapaw, “Sinners” was really just an IMAX-sized version of that sex dream we’ve all had about Michael B. Jordan trying to bite himself, at least until Kelli Weston hailed it as “a dynamic testament to Ryan Coogler’s populist impulses, his proclivity for grandiose portraiture, and his unerring insistence that no one who embraces the American project may escape its grotesque transformations.” “The Secret Agent” was just a thrilling and deeply felt display of the movies’ ability to manufacture a meaningful history of their own — an unforgettable argument that cinema can be even more valuable as a vehicle for exhuming the truth than it is as a tool for burying it — until David Sims wrote on his Letterboxd that it “whips ass.” That was the entire review.

Of course, determining the exact nature of the relationship between critics and artists has become a recurring theme at this dinner, as any number of chairs have taken the opportunity to lament the fact that critics and artists are spiritually aligned but also somehow irreconcilable; that we’re both fighting against the common enemy of mediocrity, but are fated to do so while facing directly towards each other from separate and unequal vantage points. It was just a few years ago that the great Alison Willmore stood at this very podium and quoted the art critic Peter Schjeldahl, who said that “Closeness is impossible between an artist and a critic. Each wants something from the other — the artist’s mojo, the critic’s sagacity — that belongs strictly to the audiences for their respective work; it’s like two vacuum cleaners sucking at each other.”

But with all due respect to the late Mr. Schjeldahl, who belonged to a different and more clearly demarcated era, as the once-monolithic film industry continues to shrink into a glorified niche, it’s become increasingly undeniable that artists and critics ARE the audience for each other’s respective work. Which isn’t to say that filmmakers make movies for critics, or that critics write their reviews for filmmakers, but rather to observe that we have each become the last remaining failsafes to ensure that anyone still gives a shit about the work that either of us do, and the medium that both of us still love.

Whether it’s streaming executives who insist that going to the movies is an outmoded practice (despite the overwhelming data that young audiences are the most AMC-friendly demographic), or movie theaters that refuse to mask their screens, or AI evangelists who preach that grotesquely Frankensteining stolen work into a soulless chimera of some kind is a worthy replacement for the magic of motion pictures, the viewing public has never been so aggressively conditioned to expect less — to surrender more, to put convenience before fulfillment, to be passively sated rather than actively engaged.

And yet, in spite of those obstacles, it’s because of the critics and the filmmakers in this room that the movies still remain among the most persistent bulwarks against the forces of enshittification despite all of the medium’s diminishments and defeats. And in the shadow of such enshittification, it’s never been more obvious that film without critics would be as doomed as critics without film. It’s never been more obvious that no one would challenge us if we failed to challenge each other. Perhaps even more importantly, no one would reward us either.

The future of movies — which is a microcosm for the future of everything — is a fight between people who give a shit and people who don’t. At the end of the day, I really think it’s that simple. And everyone in this room, whatever their discipline, is someone who gives a shit. Love it or hate it, “Marty Supreme” is not the kind of movie that someone makes by accident while trying to churn out content. By the same token, Richard Brody got so mad when the latest Wes Anderson movie failed to win any prizes this year that he beat a fellow NYFCC member to death with a bagel, and is only here tonight because critic-on-critic violence is legally considered to be a victimless crime.

Which brings us to the purpose of tonight’s dinner. Maybe this is as close as critics and artists are ever likely to ever get — sitting at different tables in the same oversized pan-Asian restaurant in front of a giant Quan Yin statue that Adrien Brody so confidently misidentified as Shiva last year. But, contrary to Peter Scheldahl’s words, a night like tonight reminds me that it’s not what critics and artists want from each other, but what we give to each other that matters. Yes, we give you awards in return for you giving us things to write about, but really, what we give to each other are reasons to continue giving a shit about the things we love, and the courage to insist that the things we love are still capable of giving us something meaningful in return.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.