Suddenly, with little warning, an hour into Jim Jarmusch’s 1986 existential comedy Down By Law, three gleeful prisoners descend from a rope that looks like something a child might use to exit a treehouse, and run to freedom through a sewer, laughing all the way. It’s a confusing moment, because it’s a jailbreak, an inherently cinematic process that Jarmusch heroes like Robert Bresson have turned into entire films—but Jarmusch yadda-yaddas the procedure. A few weeks ago, I asked him what motivated that decision. “I like the avoidance of those moments,” he said. “I generally really dislike biopics, and the reason why is they just take what they think are the most dramatic elements of someone’s life and put them in a row. But Michelangelo may have gotten ideas by being hung over and looking at his feet. You know what I mean? Like, why do you have to make everything so tied to drama or to these arcs? It’s a classical form, conflict, resolution, all of that. And there’s beauty in it. But there’s beauty in the avoidance of it, too, for me, of circumventing these expectations.” He laughs, then adds: “I’m quite proud of the jailbreak.”

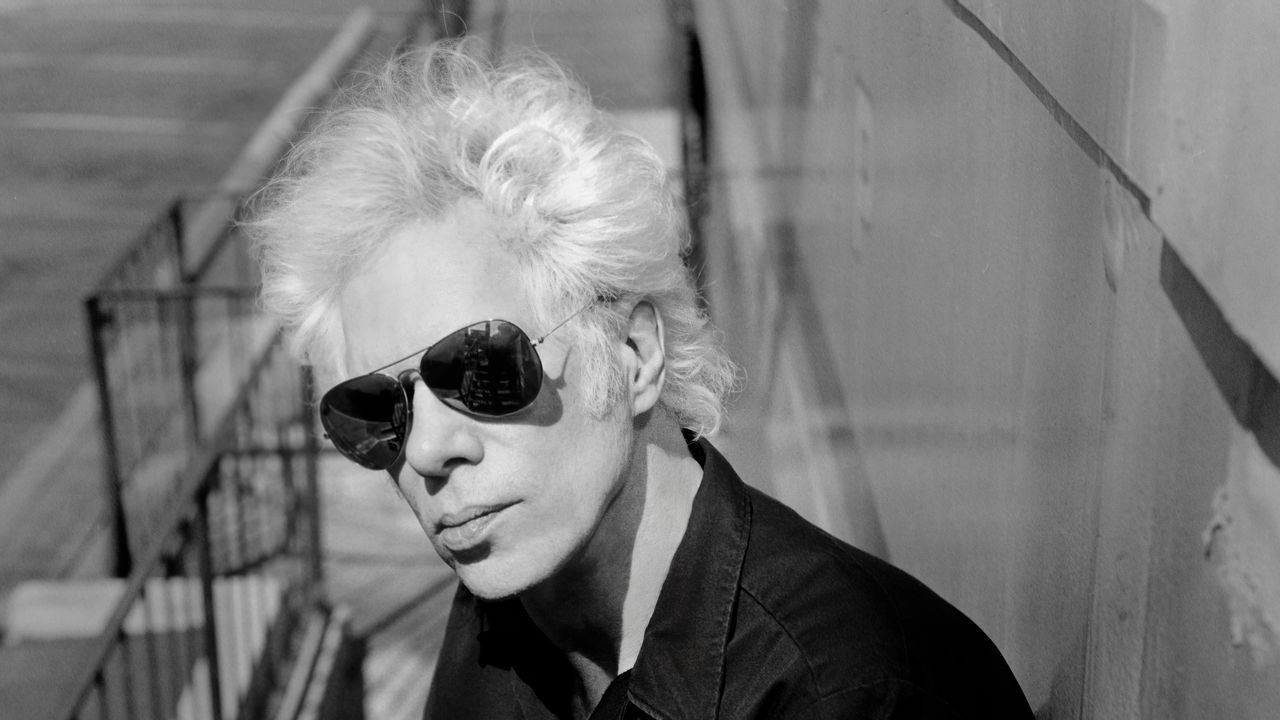

I’m speaking to Jarmusch via Zoom. He’s in his apartment in New York City’s Chinatown—72 years old, maybe a bit more gaunt, nursing a hoarse cough, but still looking very much like the impossibly cool, audacious filmmaker who practically birthed the modern American independent film movement in 1980 with Permanent Vacation. Same searching eyes behind tinted thick-framed glasses, same shock of white hair. He riffs extemporaneously, freely pulling quotes and anecdotes from Cassavettes and Lynch and Kurosawa out of the ether, as if they’re in the other room.

Jarmusch is from Ohio. His dad worked for the Goodrich rubber company in Akron, and Jim has worked as a welders’ apprentice and a spot welder and an usher at St. Mark’s Cinema in addition to his last 45 years at the vanguard of American independent film. He studied comp lit at Columbia, went to Paris in ‘75 as part of his studies and came back with incompletes once he discovered the Cinématéque. He apprenticed with Nick Ray, knew Sam Fuller and Fellini and Suzanne Schiffman, and shot his first feature on leftover black and white 35mm film stock he got from Wim Wenders, in an East 3rd Street apartment where Jean-Michel Basquiat used to crash. Jarmusch remains a 1-of-1, never quite achieving mainstream success, remaining stridently independent. “Neil Young and Iggy Pop,” Jarmusch once said, “are true to themselves, receptors and creators…[T]heir artistic expression is truly their own.” He was referring to two rockers he’s made documentaries about, but he could have been talking about himself.

His origins call to mind Andy Warhol’s; he’s a fan of Warhol’s, and in conversation, exhibits a touch of the late downtown artist’s signature blend of laconic, droll and articulate detachment and playful, achingly sincere, is-this-guy-fucking-with-me enthusiasm. Father Mother Sister Brother, Jim’s 14th film, is out this week. It’s another example of a type of movie Jarmusch essentially invented along with Richard Linklater in the early 1990s—Jarmusch with Night On Earth and Linklater with Slacker. They’re conversation films, tenuously-connected vignettes featuring two or more people talking and little else, exercises in circumventing expectations and centering the awkward silences in life, the unplayed notes.

Oscar winning legend Cate Blanchett, who has returned to Jarmusch for the first time in 22 years—since her segment of Jarmusch’s 2003 omnibus Coffee & Cigarettes—sees his films as treatises on the holistic human experience. “He loves the absurdity of being alive,” Blanchett says, “and he’s always trying to figure out, how the hell do we all find ourselves in the same room together? How are we going to work this thing out? And he does it with great love and great humor. You remember his films because they’re not merely amusing, they’re not merely beautiful, they’re not merely stunningly visual. There is a melancholy and kind of a longing and a love in them. There’s a heartbeat in them that I think is very particular to him.”